Affinity maturation: the process through which B cells mature and produce antibodies that have a greater affinity for their antigenic target. This process is more prominent when the immune response is well under way.

A receptor expressed on the surface of muscle cells at the junction between muscles and nerves. The receptor binds acetylcholine, a molecule released by the nerves that induces muscle contraction.

Enzymes that transfer phosphate groups from a donor (such as ATP) to proteins. Tyrosine kinase can become the target of an autoimmune response.

An autoimmune disease observed in infants caused by the passage of autoantibodies against Ro and/or La antigens from the mother to the baby. The disease can be very severe because these antibodies are capable of causing heart block.

An autoimmune disease caused by the presence of autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 1, a protein part of of the desmosome. Desmosomes are structures that keep cells of the skin tightly together. Antibodies disrupt this connection, resulting in the formation of blisters.

An autoimmune disease caused by the presence of autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 3, a protein part of the desmosome. Desmosomes are structures that keep cells of the skin tightly together. Antibodies disrupt this connection, resulting in the formation of blisters.

An autoimmune disease caused by the presence of autoantibodies directed against the blood platelets, which are necessary for normal blood clotting. Patients have characteristic bleeding manifestations.

An autoimmune disease caused by the presence of autoantibodies directed against the acetylcholine receptor, which is located on skeletal muscle. Patients have characteristic muscle weakness.

Aggregates of immune cells, mainly B cells and T cells, that develop in organs affected by autoimmunity, organs that normally do not contain lymphocytes.

The human leukocytes antigen (HLA) system is the MHC in the human species.

The position of a gene on a chromosome. When the same gene has different versions in different people, these versions (called "alleles") still occupy the same locus.

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a cluster of genes that make proteins expressed on the cell-surface that are involved in antigen processing and other immune functions. The MHC genes are the most polymorphic genes we have, meaning that the same gene has slightly different sequences in different people.

Any virus, bacterium, parasite, or fungus that can enter into the human body and cause disease.

A technique used to quantify proteins (such as antibodies and antigens) based on how they scatter light when put in a solution.

A technique used to determine the presence of antibodies in the patient's serum, revealed by their binding to a purified antigen of interest attached to a plastic plate. After binding to the antigen, the patient antibodies are detected by the addition of a commercially-available antibody directed against human antibodies that has been coupled to an enzyme.

A technique used to determine the presence of antibodies in the patient's serum, revealed by their binding to a purified antigen of interest attached to magnetic beads. After binding to the antigen, the patient antibodies are detected by the addition of a commercial antibody directed against human antibodies that has been coupled to a light-emitting molecule.

A technique used to determine the presence of antibodies in the patient's serum, revealed by their binding to a particular tissue substrate of interest. After binding to the tissue, the patient antibodies are detected by the addition of a commercial antibody directed against human antibodies that has been coupled to a fluorescent dye.

Immune checkpoints are molecules that normally regulate the immune response by putting a brake on T cells. When checkpoints are inhibited, T cells become unleashed and can be used to destroy cancer cells. At the same time, this inhibition of the checkpoints makes T cells more capable of causing autoimmune diseases.

T cells that recognize antigens belonging to the patient (such as thyroglobulin in he thyroid or myosin in the heart), rather than antigens in bacteria and viruses.

Several forms of alteration of the immune system where the normal balance between the various immune components is altered.

Consisting of or derived from many clones.

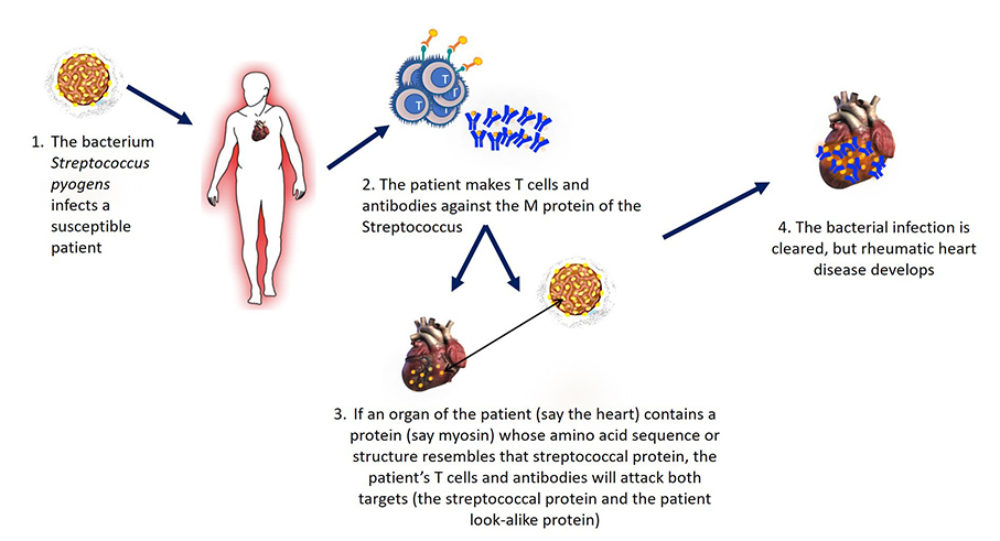

A disease initiated by infection with some Streptococcus species where the patient makes antibodies against these bacteria that however also recognize with heart antigens, such as cardiac myosin.

Also known as B cells, these lymphocytes have a surface receptor specific for one of many antigens. B cells also secrete antibodies that when directed against self components are called autoantibodies (as found in patients with autoimmune diseases).

The part of the antigen that is recognized by an antibody or a T-cell receptor.

Also known as T cells, these lymphocytes are one of the two lymphocyte types that have antigen-specific receptors on their surface and mediate adaptive immunity (the other type is the B lymphocyte).

Any molecule that can be recognized specifically by antibodies or T lymphocytes. Typically the recognition is focused on some parts of the antigen (rather than the entire antigen), which are called epitopes.

A normal component of the patient, such as a protein or a protein-nucleic acid complex, that becomes recognized by the patient's own antibodies and/or T lymphocytes during an autoimmune disease.

The type of antibodies that recognize antigens of the patient, always present in autoimmune diseases and sometimes causing them.

Proteins produced by B lymphocytes and plasma cells that recognize specific molecules called antigens.

The collection of characteristics of a person (morphological, physiological, biochemical, etc), as determined by his/her genotype and environment.

The hardening of a tissue caused by an abnormal deposition of collagen fibers. For example, sclerosis of the skin in scleroderma; and sclerosis of the kidney in diabetic patients who develop glomerular disease.

An autoimmune disease targeting the skin melanocytes and producing characteristic patches of discoloration that are disfiguring and dampen patient's self-esteem and quality of life.

An autoimmune disease predominantly targeting the thyroid gland, and mediated by autoantibodies that bind to and stimulate a receptor expressed on thyroid cells called TSH receptor.

A systemic autoimmune disease affecting the skin (dermatomyositis), the striated muscles (polymyositis), and often other targets (from the joints to the lungs).

A systemic autoimmune disease affecting the joints (with a pattern similar to rheumatoid arthritis) and a variety of other organs (ranging from kidney, heart, muscles, to the nervous system), the skin, and often other organs (such as lungs, and gastro-intestinal system).

A systemic autoimmune disease affecting the joints (with a pattern similar to rheumatoid arthritis) and a variety of other organs (ranging from kidney, heart, muscles, to the nervous system).

A systemic autoimmune disease primarily targeting the membrane (called synovium) that line peripheral joints (such as those of the hand, elbow, shoulder, knee and hip).