Leiomyosarcoma is a rare type of cancer that affects smooth muscle tissue. These tumors are most common in the abdomen, but can occur anywhere in the body, including the uterus.

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare type of cancer that forms in soft tissue — specifically skeletal muscle tissue or sometimes hollow organs such as the bladder or uterus.

A medical doctor who specializes in the management and surgery of diseases of the genitourinary tract.

A colorless crystalline solid which readily forms water-soluble polymers.

A mucous membrane

The removal and microscopic examination of a tissue sample.

Visual examination of the inside of the bladder by means of a cystoscope (Instrument that is passed through the urethra and allows visualization and biopsy of the bladder).

An imaging technique that uses beams of radiation (X-rays) to take an image of the body.

Epithelium that lines the bladder mucosa, the renal pelvis, ureters and urethra

Tubular structure that transports urine from the bladder with the urethral meatus in the vulva in women and with the urethral meatus in the glans penis in men

Tubular structure that transports urine from the renal pelvis with the bladder

The removal of tissue through the use of a cystoscope, without a surgical incision on the skin

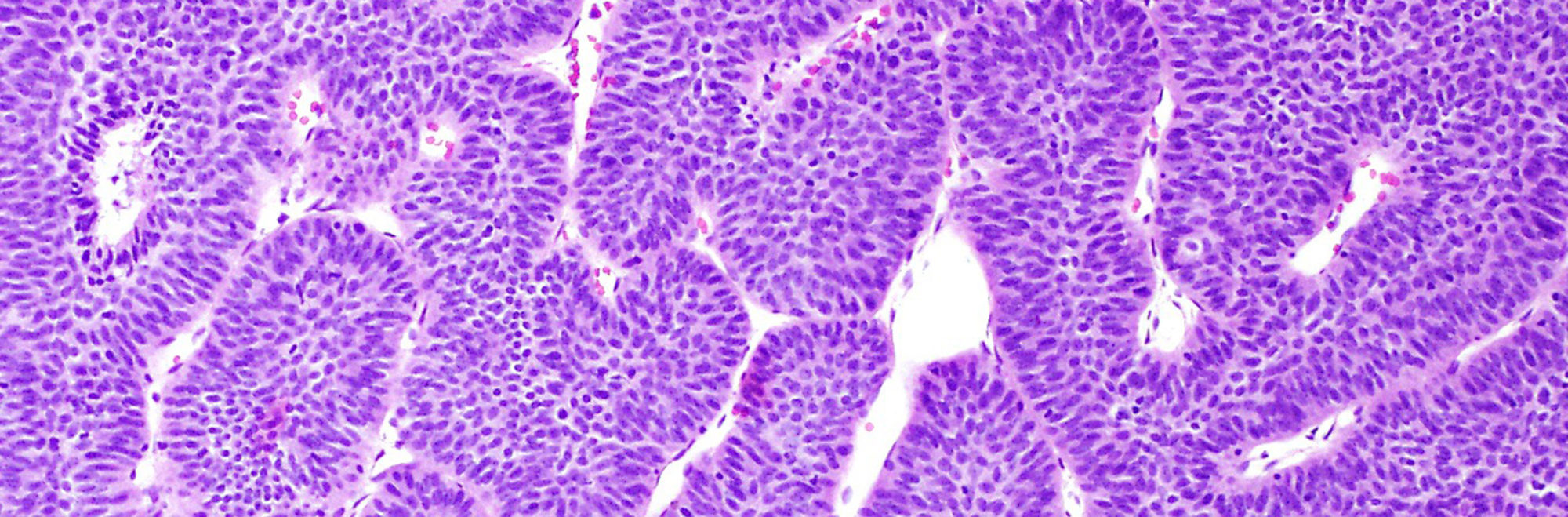

Medical subspecialty that studies tissue abnormalities caused by diseases. Biopsies and resection specimens are read and informed by “surgical pathologists”

Carcinoma that resembles cancer originating in the skin

Vessels, connective tissue and cells providing support to epithelial cells

A multidisciplinary meeting of the physicians and caretakers involved in cancer care, including pathologists, surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, radiologists, nurses and genetic counselors to discuss the treatment plans for individual patients

A mass or a lump. A tumor mass can be nonneoplastic and be due to something like swelling or inflammation. A tumor mass can also be neoplastic, and includes both benign and malignant tumors

The process by which the body reads the code in RNA to make proteins

The process by which DNA is copied to make RNA

A type of treatment that specifically targets a single molecule or pathway involved in cancer cell growth and progression

A treatment that can reach cancer cells that have potentially spread throughout the body. Examples include chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy. Systemic therapies can have side effects due to effects on normal body cells, such as hair loss or gastrointestinal distress

A disease that widely affects the entire body

Any change noted by a patient that could be caused by a disease

A physician who specializes in surgical treatment (removal) of cancer

The term for the usual treatment given for a particular disease, which is based on past research and experience proving the treatment’s efficacy and safety

A measure of how much a cancer has grown and/or spread in the body (i.e., how advanced a cancer is). The most common staging system is the TNM system, which stands for Tumor, lymph Nodes, and Metastasis. Stage ranges from 0 to 4, with stage 0 being pre-invasive disease, and stage 4 being metastatic disease. The stage is often written using Roman numerals: stage 0, stage I, stage II, stage III and stage IV. Stage is a prognostic factor, such that a high stage is associated with a poorer prognosis or outcome

The process of having a second set of doctors look at your unique medical situation to provide a second opinion on the diagnosis and/or treatment plan

Cancer that arises from epithelium but transform to look like stromal origin

Cancer arising from stroma cells

RNA molecules are a copy of the genetic information encoded in DNA, and the RNA copy is then used to create proteins

A term used to describe the balance between the risk (such as side effects) and benefit of a therapy, procedure, or other course of action

Anything that increases the risk of developing a disease. For bladder cancer, these include smoking history, age and male gender

The chance or probability of developing a disease in a given period of time

A research study in which patient records and files are reviewed to look for results (outcomes) that already occurred in the past

Resident physicians are physicians who have finished medical school and are now studying a specific area in depth, such as pathology, internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, radiology, and more

A reduction is size

Lymph nodes that drain (collect) the lymph fluid from a particular part of the body. The main regional nodes of the bladder are in the pelvis

When a cancer returns after previously having been eliminated. This can be a local recurrence in the bladder, or a distant recurrence when the cancer metastases to a new organ

A type of research study in which patients are randomly assigned into treatment groups, either to receive an experimental treatment (“intervention group”) or standard treatment (“control group”).

A physician who specializes in the use of imaging techniques, such as X-rays, mammograms, CT scans, and MRIs. This can include reviewing scans to detect a physical abnormality or mass, or for placing a needle in an exact location in order to perform a core biopsy

A treatment for some forms of cancer that uses high energy radiation to damage the DNA of the cells

Is the removal of the urinary bladder in women and the urinary bladder, prostate and seminal vesicles in men

A research study that is conducted using new patients and following their course to observe the outcome

A term used to describe continued growth of a cancer

A term that describes variation in size and shape of a cell’s nucleus

Urothelial carcinoma characterized by cells with an appearance similar to plasma cells and a pattern of single cell infiltration

A physician who specializes in the diagnosis of disease; pathologists use a microscope to examine the cells from tissue to determine if the tissue is normal or cancer

A description for how a cancer has responded to therapy, as seen under the microscope

The tissue of an organ

Cancer originated in the urothelium that forms exophytic or endophytic papillary structures (protrusions with a fibrovascular core)

Treatments given to relieve pain and symptoms rather than to cure the disease

An abnormal growth of cells that are clonal, that is, they arose from each other and share genetic material. Neoplasms can be benign or malignant

Therapy that is given to the patient before surgery to attempt to shrink the tumor size. Neoadjuvant therapy is typically chemotherapy or targeted therapy, but can also include radiation therapy

Thick muscle bundles that serve as the contractile unit that expulses the urine out during urination

Thins smooth muscle bundles located underneath the urothelium

A change in a cell’s DNA. Some mutations lead to a favorable change in a gene or a protein’s function, an unfavorable change, a loss of function, or no change at all (see also genetic mutation)

An approach to patient care that incorporates several disciplines of medicine and allows for communication between physicians and caretakers of different specialties. In bladder cancer care, this includes genetic counselors, medical oncologists, nurse navigators, pathologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and oncologic urologists. By sitting everyone down at one time, medical providers can better coordinate care, leading to better patient care

An imaging technique that uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to take pictures of tissue deep in the body

Classification of cancer based on its gene expression. There are 2 main molecular subtypes in bladder cancer, luminal and basal

The process by which a cell divides into two cells. Under the microscope, dividing cells can be identified by their exposed chromosomes (DNA)

A device used by pathologists to examine tissue on slides; the microscope magnifies the tissue so that pathologist can examine the individual cells and make a diagnosis

Morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma forming micropapillae. It is considered a clinically aggressive deviant morphology

Tumor established in a distant place from its origin. Most common metastatic sites are lymph nodes, lungs, liver, brain, and bone

A doctor specialized in the treatment of cancer using chemotherapy, immune check point inhibitors, and targeted therapy

A lump or swelling. A mass can be due to excess fluid or an abnormal growth of cells; the growth of cells can be benign or malignant

The ‘edge’ of specimen containing a rim of normal-appearing tissue around the tumor. Pathologists evaluate the margin tissue under the microscope to see if the tumor has been entirely removed. “Negative” or clean margins means that all of the tumor was removed. “Positive” or involved margins means that the tumor was not entirely removed and additional therapy may be necessary

Cancer cells with the ability to invade surrounding tissue and with the potential to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and distant organs

Tumor cells entering the lymphatic system and in-route to lymph nodes

Part of the immunologic system where antigens are presented to immune cells to develop an immunologic response. In cancer, lymph nodes are where the tumor cells go after they leave the primary tumor

Cancer that is expected to progress more slowly that high-grade cancer

Cancer that has not yet spread to nearby tissues (by direct invasion) or to distant organs (by metastasis)

Connective tissue immediately underneath the urothelium

Cancer that has invaded into the stroma and can give rise to metastases

Refers to therapy applied using intravesical instillation of drugs or BCG

A pattern of growth where the cancer cells grow into (invade) the surrounding tissues (see also infiltrating)

Something that occurs during an operation. For instance, a frozen section is done intraoperatively

The result of the presence of immune cells (“inflammatory” cells) to a part of the body. Areas of the body that are inflamed often look swollen and red

A pattern of growth where the cancer cells grow into (invade) the surrounding tissues (see also invasive).

A type of treatment that uses the immune system to fight cancer; these therapies target proteins expressed by immune cells or on the cancer cell

A type of laboratory test that can detect the proteins expressed by a cell. The test uses special antibodies (“immunostains”) that each binds to a particular protein in question; the immunostain will change the color of the tissue to show whether a protein is present

The body’s natural defense against infection with microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses. The immune cells are constantly on the lookout for cells that look “foreign.” In addition to microorganism, immune cells can also recognize cancer cells as “foreign,” since the cancer cells may express abnormal proteins. In this way, the immune system can sometimes be a part of the body’s attack against cancer

Cancer that is expected to behave aggressively

Relating to appearance of cells and tissues under the microscope

The area of tissue that is seen at a microscope’s highest magnification (i.e., the most “zoomed in”)

Blood in the urine

Blood in semen

A type of dye that is applied to tissue sections so that the cells absorb the color and can be seen with the eye when looking under the microscope. This dye turns the nuclei blue and the cytoplasm pink

A histologic description of how closely the cancer cells resemble their normal cell of origin

A small, thin rectangular piece of glass where tissue slices from a biopsy or a surgical specimen are placed and stained with dye so that the tissue can be evaluated under a microscope

A mutation in DNA that is present at birth and that can be transferred from parent to child

A test of a patient’s DNA to look for specific gene mutations or other abnormalities that might cause cancer or other conditions

A change in a cell’s DNA. Some mutations lead to a favorable change in gene or protein’s function, an unfavorable change, a loss of function, or no change at all (see also mutation)

A meeting between a patient and a medical geneticist or counselor to discuss the potential impact of a genetic test result on the health of a patient and for their family

A laboratory test that analyzes the expression of multiple genes to characterize what proteins tumor cells are creating

A single sequence of DNA that codes for a protein

A method that pathologists can perform intra-operatively (i.e., while a surgery is underway) to quickly freeze a piece of tissue from the patient in order to take thin slices and make a slide to evaluate “in real time” while the surgery is still ongoing. This is sometimes performed on lymph nodes or margins to tell the surgeon whether there are cancer cells there. The results are only preliminary, however, and must be confirmed with review of the final FFPE sections

A term used to describe how fresh tissue samples are processed and stored so that slides of the tissue can be made and examined by a pathologist. The fresh tissues are “fixed” in a preservative called formalin, so that the tissues will not degrade or decompose. They are then “embedded” into paraffin wax, which means they are placed into a little block or wax similar to candle wax so that they can be easily sliced into thin slices and placed on a glass slide for a pathologist to review

The medical history of all of the biological (blood-related) members of a family; this family medical history can show patterns of shared diseases. Because you share genes with your family members, a “positive family history” of certain diseases may be considered a risk factor for an individual to develop the disease.

A positive result for a test that should actually be negative (i.e., an incorrect test result that states a person is positive for disease, which the person is actually disease-free)

A negative result for a test that should actually be positive (i.e., an incorrect test result that states a person is disease-free, which the person actually has the disease)

The layer of cells that lines the outside of the body, lines the inside of the body cavities, and lines the outside and inside of body organs. Epithelium is one of four types of tissues in the body; the other three types are connective tissue (like fat and fibrous tissue), muscle tissue, and neural/nervous system tissue. The epithelium lining each of the surfaces in the body has different names; for instance, the epithelium lining the outside of the body is called skin, and the epithelium lining the inside of the chest cavity is called the pleura. The epithelium that lines the urinary system is called urothelium

A type of cell in the body that makes up many different tissue types, including urothelium in the bladder. Epithelial cells in other parts of the body line the body surface (such as the “squamous epithelium” of the skin) and the body cavities. The epithelial cell is the cell or origin of carcinomas

Swelling of a part of the body from excess fluid

The molecule which contains all of your genes, located within a cell’s nucleus … a long, complex molecule with which your genes are encoded

Synonym with muscularis propria

The portion of a cell outside the nucleus, but still within the cell membrane

A consultation in pathology occurs when a specimen is sent to a second (or sometimes third) institution to review the findings. This can occur when other pathologists need assistance with a particularly challenging or rare case, or if a patient or clinician would like a second opinion on a case.

A study organized by a hospital, organization, or other group to systematically and thoroughly investigate a new medication, technique, or other approach to treatment. Clinical trials are extensively monitored to make sure that they are conducted in a safe, ethical, and equitable manner

Flat carcinoma that is non-invasive

drugs used to kill tumor cells

Cancer arising from epithelial cells

A neoplastic (clonal) growth of cells with the potential to metastasize (spread throughout the body). Cancers can arise from epithelial cells (“carcinomas”), melanocytes (“melanomas"), stromal or connective tissue cells (“sarcomas”), and lymphoid cells (“lymphomas and leukemias”)

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) a live attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is currently an agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for primary therapy of carcinoma in situ, non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, and carcinoma invading the lamina propria (stage pT1) of the bladder.

A tubular structure that carry blood both to and from various parts of the body. This includes arteries, veins, and capillaries.

Pelvic reservoir of urine.

Any chemical or protein created by the body that can be measured, and can be used to provide useful information such as whether a cancer is growing or shrinking during treatment. Biomarkers can also provide information about the prognosis of a cancer (prognostic biomarker), as well as whether a cancer will respond to certain therapies (predictive biomarker).

Non-cancerous. A benign tumor cannot invade nearby tissues or spread to other parts of the body

Tumor cells invading blood vessels to travel to a distant location and form a metastasis

Adjuvant therapy is any treatment given in addition to surgery. It can include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other treatment. This is in contrast to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is given before surgery