Historically defined as disease recurrence within 6 months of completion of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, although this is now more broadly applied to also include patients progressing within 6 months after multiple lines of chemotherapy.

(of cells or tissues) Obtained from the same individual.

The degree to which a substance (a toxin or poison) can harm humans.

This chemotherapy technique delivers chemotherapy drugs directly into the abdominal cavity through a catheter (thin tube).

A surgical procedure that removes your uterus through an incision in your lower abdoman.

Also known as a BSO, is a surgical procedure in which both of the ovaries and the fallopian tubes are removed.

A surgical procedure designed to remove the omentum, which is a thin fold of abdominal tissue that encases the stomach, large intestine and other abdominal organs.

Removal of the affected ovary and fallopian tube.

A primary ovarian tumor with features similar to those of the kidney tumor of the same name.

Also called sonography or diagnostic medical sonography, is an imaging method that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of structures within your body. The images can provide valuable information for diagnosing and treating a variety of diseases and conditions.

A multidisciplinary meeting of the physicians and caretakers involved in cancer care, including pathologists, surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, radiologists, nurses and genetic counselors to discuss the treatment plans for individual patients.

A mass or a lump. A tumor mass can be nonneoplastic and be due to something like swelling or inflammation. A tumor mass can also be neoplastic, and includes both benign and malignant tumors.

An inflammatory mass found in the fallopian tube, ovary and adjacent pelvic organs.

The process by which the body reads the code in RNA to make proteins.

The process by which DNA is copied to make RNA.

Thecomas are stromal tumors containing a significant number of cells with appreciable cytoplasm resembling to varying degrees theca cells.

A type of treatment that specifically targets a single molecule or pathway involved in cancer cell growth and progression.

A treatment that can reach cancer cells that have potentially spread throughout the body. Examples include chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy. Systemic therapies can have side effects due to effects on normal body cells, such as hair loss or gastrointestinal distress.

A disease that widely affects the entire body.

Any change noted by a patient that could be caused by a disease.

A mature teratoma composed either exclusively or predominantly of thyroid tissue.

Presence of luteinized cells in the ovarian stroma, typically associated with stromal hyperplasia.

A non-neoplastic, benign proliferation of ovarian stromal cells without associated luteinized stromal cells.

A tumor composed entirely of cells resembling steroid-secreting cells that lack Reinke crystals.

The term for the usual treatment given for a particular disease, which is based on past research and experience proving the treatment’s efficacy and safety.

A measure of how much a cancer has grown and/or spread in the body (i.e., how advanced a cancer is). The most common staging system is the TNM system, which stands for Tumor, lymph Nodes, and Metastasis. FIGO stage is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics system.

A gene mutation that occurs spontaneously in the body tissues or in the cancer cells that cannot be passed on to offspring (i.e., it cannot be inherited).

An undifferentiated neoplasm, predominantly composed of small cells, but occasionally with a large cell component, and which is often associated with paraneoplastic hypercalcemia. The tumor is unrelated to small cell carcinoma of neuroendocrine (pulmonary) type.

A benign, stromal tumor containing cells with signet-ring morphology but without intracytoplasmic mucin, glycogen or lipid, in a background fibromatous stroma.

An uncommon, sex cord-stromal tumor with a distinctive pattern of simple and complex annular tubules.

Tumors are composed of variable proportions of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells and in the case of moderately and poorly differentiated neoplasms, primitive gonadal stroma and sometimes heterologous elements.

A neoplasm composed of Sertoli cells arranged in a variety of patterns, but most commonly as hollow or solid tubules.

These tumors are characterized by epithelial cell types resembling those of the fallopian tube, including ciliated cells. The epithelial component may be associated with a prominent component of stromal cells (cystadenofibroma, adenofibroma), may lack a stromal component (cystadenoma) or be entirely a surface papillary lesion (surface papilloma). Combinations of these growth patterns occur.

A carcinoma composed predominantly of serous and endocervical-type mucinous epithelium. Foci containing clear cells and areas of endometrioid and squamous differentiation are not uncommon.

A benign cystic neoplasm with two or more Müllerian cell types, all accounting for at least 10% of the epithelium. Rare tumors have more prominent fibrous stroma (adenofibroma).

The process of having a second set of doctors look at your unique medical situation to provide a second opinion on the diagnosis and/or treatment plan.

A term used to describe testing used to look for a disease before it has caused symptoms.

A benign, stromal tumor composed of admixed rounded and spindled cells, arranged in cellular nodules in a hypocellular, edematous or collagenous background stroma.

A cancer that arises from the connective tissue of the body. Examples include angiosarcoma (arising from blood vessels) and leiomyosarcoma (arising from smooth muscle cells).

mRNA molecules are a copy of the genetic information encoded in DNA, and the RNA copy is then used to create proteins.

Anything that increases the risk of developing a disease. For ovarian cancer, these include family history and age.

The chance or probability of developing a disease in a given period of time.

A research study in which patient records and files are reviewed to look for results (outcomes) that already occurred in the past.

Resident physicians are physicians who have finished medical school and are now studying a specific area in depth, such as pathology, internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, radiology, and more.

A reduction is size.

When a cancer returns after previously having been eliminated. This can be a local recurrence in the area where the cancer was first detected, or a distant recurrence when the cancer metastases to a new organ.

A type of research study in which patients are randomly assigned into treatment groups, either to receive an experimental treatment (“intervention group”) or standard treatment (“control group”).

A treatment for some forms of cancer that uses high energy radiation to damage the DNA of the cells. This is a form of local therapy

A physician who specializes in using targeted radiation therapy to kill tumor cells in a specific area.

Round microscopic calcific collections.

A research study that is conducted using new patients and following their course to observe the outcome.

A term used describe treatments that are done before a disease occurs to prevent the disease from happening.

A measure of how rapidly a tumor is growing by assessing how many cells are dividing. The measure ranges from 0% (no cells dividing) to 100% (all cells dividing). (See also Ki67.)

A term used to describe continued growth of a cancer.

A test result that can be used to help predict a patient’s prognosis. For instance, the expression of the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) are favorable prognostic features.

A term used to describe the expected outcome of a cancer or disease (i.e., favorable or unfavorable).

The protein responsible for binding to and detecting progesterone in the body; the receptor is located in the nucleus of many cell types. Some cancers express the progesterone receptor and are termed “hormone receptor positive” cancers.

A sex hormone made by the body that is part of the estrogen signaling pathway.

Before menopause.

One or more hyperplastic nodules of large, luteinized cells developing during the latter half of pregnancy and involuting spontaneously during the puerperium.

After menopause.

A hormonal disorder causing enlarged ovaries with small cysts on the outer edges. The cause of polycystic ovary syndrome isn't well understood, but may involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Symptoms include menstrual irregularity, excess hair growth, acne, and obesity.

A term that describes variation in size and shape of a cell’s nucleus.

A type of imaging study that uses a radioactive element attached to a sugar molecule to detect parts of the body with rapidly growing cells (which consume more sugar), such as cancer cells.

A method of processing tissue to evaluate it under the microscope; the tissue is formalin fixed and paraffin embedded so that it can be thinly sliced and made into slides to review under a microscope.

Near and around the time of menopause.

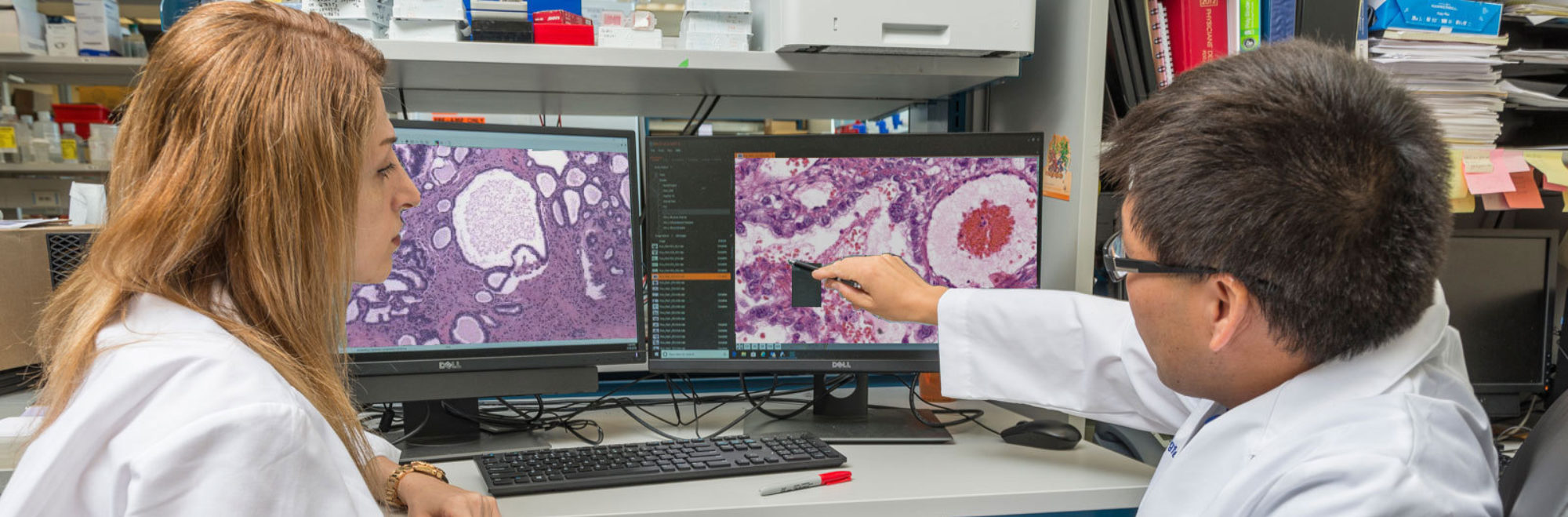

A physician who specializes in the diagnosis of disease; pathologists use a microscope to examine the cells from tissue to determine if the tissue is normal or cancer.

A description for how a cancer has responded to therapy, as seen under the microscope.

Treatments given to relieve pain and symptoms rather than to cure the disease.

Ovarian torsion is a condition that occurs when an ovary twists around the ligaments that hold it in place. Ovarian torsion can cause severe pain and other symptoms because the ovary is not receiving enough blood.

A surgical procedure where the ovary is removed.

Hidden, or not known.

The part of a cell that contains the cell’s genetic material, DNA.

The size ratio of the nucleus to the cytoplasm. In many cancers, the nuclear becomes markedly and abnormally enlarged, leading to the abnormal feature of a “high N:C ratio.”

A histologic measure of how closely a cancer cell nucleus resembles that of a normal cell, or a measure of how abnormal a cancer nuclear is. It is generally graded as 1 (resembles normal), 2 (moderately abnormal), and 3 (markedly abnormal).

Relating to the nucleus of a cell.

A non-invasive tumor displaying a nonhierarchical branching architecture featuring micropapillary and/or cribriform patterns composed of rounded cells with scant cytoplasm and moderate nuclear atypia.

Peritoneal lesions associated with serous borderline tumor were originally classified as “non-invasive” or “invasive" implants based on whether the lesions were confined to the surface of organs (noninvasive) or infiltrated the underlying tissue (invasive). Implants that display hierarchically branching papillae or detached clusters of cells associated with non-fibrotic stroma that do not invade have been termed “epithelial-type non-invasive implants,” whereas, those composed of clusters of cells embedded in reactive-appearing or dense fibrous tissue that overshadow the epithelial component and appear “tacked on” to the peritoneal surface, have been termed “desmoplastic-type non-invasive implants.” Single cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm may be present in the stroma in the latter type but are not indicative of invasion.

An abnormal growth of cells that are clonal, that is, they arose from each other and share genetic material. Neoplasms can be benign or malignant.

Therapy that is given to the patient before surgery to attempt to shrink the tumor size. Neoadjuvant therapy is typically chemotherapy or targeted therapy, but can also include hormonal therapy or radiation therapy.

A change in a cell’s DNA. Some mutations lead to a favorable change in a gene or a protein’s function, an unfavorable change, a loss of function, or no change at all (see also genetic mutation).

An approach to patient care that incorporates several disciplines of medicine and allows for communication between physicians and caretakers of different specialties. In ovarian cancer care, this includes genetic counselors, medical oncologists, nurse navigators, pathologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and surgical oncologists. By sitting everyone down at one time, medical providers can better coordinate care, leading to better patient care.

A malignant epithelial tumor composed of gastrointestinal-type cells containing intra-cytoplasmic mucin.

A benign, cystic tumor lined by mucinous gastrointestinal-type epithelium or rarely, having prominent fibrous stroma (adenofibroma).

An imaging technique that uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to take pictures of tissue deep in the body.

A tumor with two or more types of malignant, primitive, germ cell components. The most common admixture is that of dysgerminoma and yolk sac tumor.

A count of number of dividing cells in a sample. Mitotic counts are generally measured by number of mitotic cells per 10 high power fields (HPF). The more mitotic cells present, the faster the cells are growing.

The process by which a cell divides into two cells. Under the microscope, dividing cells can be identified by their exposed chromosomes.

A device used by pathologists to examine tissue on slides; the microscope magnifies the tissue so that pathologist can examine the individual cells and make a diagnosis.

Mucinous borderline tumor with microinvasion is defined as small foci of stromal invasion measuring less than 5 mm in greatest linear extent, with no requirement regarding the number of such foci allowed in a given tumor. It is characterized by single cells, glands, clusters/nests, small foci of confluent glandular or cribriform growth displaying mild to moderate atypical mucinous epithelial cells within the stroma. Similar growth patterns with cells displaying more marked cytological atypia should be classified as “microinvasive carcinoma”.

The focus of tumor cells in the stroma occupying most of the field measures < 5 mm and represents low-grade serous carcinoma.

For serous borderline tumor, the term has been applied to clusters of cells in the stroma with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, similar to the eosinophilic cells on the surface of papillae, that measure < 5 mm in greatest dimension. These cells are less likely to express estrogen and progesterone receptors and have a significantly lower Ki-67 labelling index, suggesting they may be terminally differentiated or senescent.

A rare, benign, ovarian tumor which is probably of stromal origin and characterized by a distinctive microcystic appearance.

The spread of and presence of cancer cells that have spread to other organs in the body outside of the primary site.

A natural process during which a women ceases to have a menstrual period; this typically occurs in the late 40s-50s. The ovaries no longer ovulate (i.e., no longer produce eggs) and no longer produce estrogen hormone.

Triad of benign ovarian tumor with ascites and pleural effusion that resolves after resection of the tumor. Ovarian fibromas constitute the majority of the benign tumors seen in Meigs syndrome.

A doctor specialized in the treatment of cancer using hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy.

A lump or swelling. A mass can be due to excess fluid or an abnormal growth of cells; the growth of cells can be benign or malignant.

See carcinosarcoma

An ovarian carcinoma usually of transitional cell type, resembling an invasive urothelial carcinoma. Rarely, the tumor is of squamous type. In either case the tumors are associated with a benign or borderline/atypical proliferative Brenner tumor.

Cancer cells with the ability to invade surrounding tissue and with the potential to metastasize (spread) to lymph nodes and distant organs.

The presence of cancer cells spreading into lymphatic channels.

A type of white blood cell belonging to the immune system. Lymphocytes have many functions, including fighting viruses and cancer.

The small channels that carry the lymph fluid throughout the body and drain through lymph nodes.

Small organs comprised of groups of lymphocytes (immune cells) that filter the lymph fluid that flows through the lymphovascular or lymphatic channels through the body. Cancers often first use the lymphatic channels to spread through the body.

An invasive carcinoma, usually with distinctive patterns showing low-grade malignant cytological atypia.

A steroid cell tumor composed of Leydig cells, as proven by the presence of cytoplasmic crystals of Reinke. The diagnosis is occasionally tenable in the absence of crystals when other classic features are present.

Refers to metastatic signet-ring cell carcinomas, which may originate from many anatomic sites, stomach most commonly.

An immunostain that marks a gene that is involved in cell proliferation or growth. The degree of Ki67 labeling in a cancer cell correlates to how quickly the tumor is growing and how aggressive it is. The measure ranges from 0% (no cells dividing) to 100% (all cells dividing). See also proliferation index.

A distinctive type of granulosa cell tumor that occurs mainly in children and young adults.

Implants display the features of invasion, specifically small, solid nests of cells surrounded by a space, micropapillae and/or cribriform growth, behave in a similar manner to clear-cut invasive carcinoma. As such, invasive implants are equal to invasive low-grade serous carcinoma.

A pattern of growth where the cancer cells grow into (invade) the surrounding tissues (see also infiltrating).

Something that occurs during an operation. For instance, a frozen section is done intraoperatively.

The result of the presence of immune cells (“inflammatory” cells) to a part of the body. Areas of the body that are inflamed often look swollen and red.

A pattern of growth where the cancer cells grow into (invade) the surrounding tissues (see also invasive).

A type of treatment that uses the immune system to fight cancer; these therapies target proteins expressed by immune cells or on the cancer cell.

A type of laboratory test that can detect the proteins expressed by a cell. The test uses special antibodies (“immunostains”) that each binds to a particular protein in question; the immunostain will change the color of the tissue to show whether a protein is present. Examples include immunohistochemistry to look for the expression of the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) in ovarian cancer cells.

The body’s natural defense against infection with microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses. The immune cells are constantly on the lookout for cells that look “foreign.” In addition to microorganism, immune cells can also recognize cancer cells as “foreign,” since the cancer cells may express abnormal proteins. In this way, the immune system can sometimes be a part of the body’s attack against cancer.

A teratoma containing variable amounts of immature (typically primitive/embryonal neuroectodermal) tissues, including, in its most primitive forms, embryoid bodies.

A receptor protein that binds hormones within a cell in order to affect changes within the cell. Tumors with high numbers of hormone receptors need hormones to grow.

A substance released into the blood that influence how other tissue behave and grow. Examples include estrogen, progesterone, and androgen.

A form of systemic treatment that blocks hormones from getting to the cancers that have hormone receptors.

Relating to appearance of cells and tissues under the microscope.

A steroid cell tumor composed of Leydig cells. Ovarian Leydig cell tumors have been divided into two subtypes by some pathologists, the hilus cell tumor and the Leydig cell tumor, nonhilar type. The former, which is much more common, originates in the ovarian hilus from hilar Leydig cells, which have been identified in 80–85% of adult ovaries.

The area of tissue that is seen at a microscope’s highest magnification (i.e., the most “zoomed in”).

A carcinoma composed of epithelial cells displaying papillary, glandular (often slit-like) and solid patterns with high-grade nuclear atypia.

A type of dye that is applied to tissue sections so that the cells absorb the color and can be seen with the eye when looking under the microscope. This dye turns the nuclei blue and the cytoplasm pink.

A histologic description of how closely the cancer cells resemble their normal cell of origin. In general, the overall grade score is calculated by looking at the mitotic rate, the nuclear grade or atypia, and the degree of gland formation. The final grade will be either grade 1, 2 or 3 or low-grade and high-grade. In general, a higher tumor grade is associated with more aggressive behavior.

A tumor consisting of a mixture of immature sex cord cells and germ cells which can be viewed as an “in situ” form of malignant germ cell tumor.

A small, thin rectangular piece of glass where tissue slices from a biopsy or a surgical specimen are placed and stained with dye so that the tissue can be evaluated under a microscope.

Tissues in the body that make protein secretions; glands are shaped like small round structures. Cancers that arise from glands are called “adenocarcinomas” (see also mammary gland).

A mutation in DNA that is present at birth and that can be transferred from parent to child.

A test of a patient’s DNA to look for specific gene mutations or other abnormalities that might cause cancer or other conditions.

A change in a cell’s DNA. Some mutations lead to a favorable change in gene or protein’s function, an unfavorable change, a loss of function, or no change at all (see also mutation).

A member of the healthcare team specialized in diagnosing and interpreting genetic test results. A geneticist might be consulted to help understand germline or somatic mutations.

A meeting between a patient and a medical geneticist or counselor to discuss the potential impact of a genetic test result on the health of a patient and for their family.

A sequence of nucleotides in DNA that encodes the synthesis of a gene product, either RNA or protein.

A method that pathologists can perform intra-operatively (i.e., while a surgery is underway) to quickly freeze a piece of tissue from the patient in order to take thin slices and make a slide to evaluate “in real time” while the surgery is still ongoing. The results are only preliminary, however, and must be confirmed with review of the final FFPE sections.

A term used to describe how fresh tissue samples are processed and stored so that slides of the tissue can be made and examined by a pathologist. The fresh tissues are “fixed” in a preservative called formalin, so that the tissues will not degrade or decompose. They are then “embedded” into paraffin wax, which means they are placed into a little block or wax similar to candle wax so that they can be easily sliced into thin slices and placed on a glass slide for a pathologist to review.

A physiological cyst lined by granulosa cells, usually underlain by theca cells.

A benign stromal tumor composed of spindled to ovoid fibroblastic cells producing collagen.

The medical history of all of the biological (blood-related) members of a family; this family medical history can show patterns of shared diseases. Because you share genes with your family members, a “positive family history” of certain diseases may be considered a risk factor for an individual to develop the disease.

A primitive malignant germ cell tumor characterized by a variety of distinctive histological patterns, some of which recapitulate phases in the development of the normal yolk sac.

A rare, primitive, germ cell neoplasm that shows rudimentary epithelial differentiation and is morphologically identical to its testicular counterpart.

The protein responsible for binding to and detecting estrogen in the body; the receptor is located in the nucleus of many cell types. Many gynecologic cancers express the estrogen receptor.

The major female sex hormone, responsible for many physiologic functions in the body. Estrogen is made by the ovaries and adrenal gland. Estrogen causes the normal growth of many cell types. Some cancers require estrogen to grow.

The layer of cells that lines the outside of the body, lines the inside of the body cavities, and lines the outside and inside of body organs. Epithelium is one of four types of tissues in the body; the other three types are connective tissue (like fat and fibrous tissue), muscle tissue, and neural/nervous system tissue. The epithelium lining each of the surfaces in the body has different names; for instance, the epithelium lining the outside of the body is called skin, and the epithelium lining the inside of the chest cavity is called the pleura.

A type of cell in the body that makes up many different tissue types that line the body surface (such as the “squamous epithelium” of the skin) and the body cavities. The epithelial cell is the cell or origin of carcinomas.

A malignant, epithelial tumor resembling endometrioid carcinoma of the uterine corpus.

Endometrioid cystadenoma is a cystic lesion lined by benign endometrioid epithelium lacking the stroma, typical vasculature and other stigmata of endometriosis. When associated with a dense fibromatous component the tumor is an endometrioid adenofibroma.

Cystic forms of endometriosis. They may or may not be associated with endometriosis elsewhere in the pelvis.

Endometriosis occurs when tissue that normally lines the uterus, known as endometrium, grows in areas outside the uterus, such as on the ovaries or fallopian tubes.

Swelling of a part of the body from excess fluid (see also lymphedema).

A primitive germ cell tumor composed of cells showing no specific pattern of differentiation

The molecule which contains all of your genes, located within a cell’s nucleus, a long, complex molecule with which your genes are encoded.

A tumor composed exclusively of mature tissues derived from two or three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm). Tumors are usually cystic (mature cystic teratoma), but rarely solid (mature solid teratoma).

The portion of a cell outside the nucleus, but still within the cell membrane.

A type of imaging that uses X-rays to take 3-dimensional images.

A cystic corpus luteum > 3 cm in diameter.

A consultation in pathology occurs when a specimen is sent to a second (or sometimes third) institution to review the findings. This can occur when other pathologists need assistance with a particularly challenging or rare case, or if a patient or clinician would like a second opinion on a case.

A study organized by a hospital, organization, or other group to systematically and thoroughly investigate a new medication, technique, or other approach to treatment. Clinical trials are extensively monitored to make sure that they are conducted in a safe, ethical, and equitable manner.

A malignant tumor composed of clear, eosinophilic and hobnail cells, displaying a combination of tubulocystic, papillary and solid patterns.

A tumor composed of glands or cysts lined by bland cuboidal to flattened cells with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm embedded in a fibromatous stroma.

A systemic medication used to treat cancer that kills cells that are dividing. Sometimes this results in undesired side effects, such as hair loss, because the chemotherapy drugs also kill normal body cells that are dividing.

Biphasic neoplasm composed of high-grade, malignant, epithelial and mesenchymal elements.

A non-invasive, clonal proliferation of epithelial cells that has does not have the capacity to invade into the normal tissue or to spread through the body. This is sometimes called “pre-cancer.”

A type of cancer arising from an epithelial cell.

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms that resemble carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract.

A neoplastic (clonal) growth of cells with the potential to metastasize (spread throughout the body). Cancers can arise from epithelial cells (“carcinomas”), melanocytes (“melanomas"), stromal or connective tissue cells (“sarcomas”), and lymphoid cells (“lymphomas and leukemias”).

Follicle-like small eosinophilic fluid-filled punched out spaces between granulosa cells. The granulosa cells are usually arranged haphazardly around the space.

A member of the mucin family glycoproteins. Testing of CA-125 blood levels has been proposed as useful in treating ovarian cancer.

A tumor composed of nests of bland, transitional-type cells (resembling urothelial cells) within a fibromatous stroma.

A human tumor suppressor gene responsible for repairing DNA. BRCA2 germline mutation is related to hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome.

A human tumor suppressor gene responsible for repairing DNA and regulating transcription. BRCA1 germline mutation is related to hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome.

A tubular structure that carry blood both to and from various parts of the body. This includes arteries, veins, and capillaries.

Any chemical or protein created by the body that can be measured, and can be used to provide useful information such as whether a cancer is growing or shrinking during treatment. Biomarkers can also provide information about the prognosis of a cancer (prognostic biomarker), as well as whether a cancer will respond to certain therapies (predictive biomarker).

A surgical procedure in which a surgeon removes both ovaries.

Involving “both sides”, such as both ovaries and fallopian tubes. This is in contrast to unilateral, which means on one side only.

Non-cancerous. A benign tumor cannot invade nearby tissues or spread to other parts of the body.

Non-invasive tumors that display greater epithelial proliferation and cytological atypia than benign serous tumors but less than low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC).

A non-invasive, proliferative, epithelial tumor composed of more than one epithelial cell type, most often serous and endocervical-type mucinous; however, endometrioid, and less often, clear cell, transitional or squamous may be seen.

Tumors composed of mild to moderately atypical gastrointestinal-type, mucincontaining epithelial cells that show proliferation greater than that seen in benign mucinous tumors. Stromal invasion is absent.

A solid or cystic tumor composed of crowded glands lined by atypical endometrioid-type cells and lacking destructive stromal invasion and/or confluent glandular growth.

Clear cell adenofibromatous tumors with atypia of the glandular epithelium but without stromal invasion.

A neoplasm of transitional cell type (resembling non-invasive, low-grade, urothelial neoplasms) displaying epithelial proliferation beyond that seen in benign Brenner tumors and lacking stromal invasion.

Ascites is the abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen. It can be caused by cancer such as ovarian cancer.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is a glycoprotein that is produced in early fetal life by the liver and by a variety of tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatoblastoma, and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the ovary and testis.

A low-grade malignant, sex cord-stromal tumor composed of granulosa cells often with a variable number of fibroblasts and theca cells.

Adjuvant therapy is any treatment given in addition to surgery. It can include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other treatment. This is in contrast to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is given before surgery.

A rare biphasic tumor with malignant mesenchymal and benign to atypical epithelial components.

A biphasic tumor composed of an admixture of Müllerian epithelium and stroma, both components being benign.

A type of carcinoma (cancer) that arises from glandular epithelial cells.

Analysis to determine the presence, absence, or quantity of one or more components.

The collection of excess amounts of fluid in the abdominal cavity (belly). It often is a sign that the cancer has spread to either the liver or the portal vein that goes to the liver. If normal liver function is affected, a complex set of biochemical checks and balances is disrupted and abnormal amounts of fluid are retained.

Usually a protein or carbohydrate substance capable of stimulating an immune response.

Any of a large number of proteins that are produced normally by specialized B cells after stimulation by an antigen and act specifically against the antigen in an immune response.

A condition marked by a diminished appetite and aversion to food. Often results in physical signs of wasting.

A radiographic technique used to visualize blood vessels. A contrast medium (a dye) is usually injected into the vessels to make them appear white on the x-rays.

A condition characterized by a deficiency in red blood cells. This can lead to fatigue, among other symptoms.

Cancer cells that divide rapidly and revert to an undifferentiated form with no orientation to one another.

Chemotherapy given to patients after their cancers have been surgically removed. It is a secondary treatment given to supplement surgical treatment. (see Neoadjuvant chemotherapy)

A benign (non-cancerous) tumor made up of cells that form glands (collections of cells surrounding an empty space).

A pus-filled cavity.

A series of x-ray pictures taken of the abdomen by a machine that encircles the body like a giant tube. Computers are then used to generate cross-sectional images of the inside of the body.