An inherited genetic variation in DNA that you are born with

Third Degree Relatives - First cousins, great-aunts and uncles

Second Degree Relatives - Aunts, uncles, grandparents, nieces and nephews

First Degree relatives - Blood relatives in your immediate family: parents, children, and siblings

Also known as a pancreatoduodenectomy, the Whipple procedure is the surgery typically performed to remove cancers of the head of the pancreas (the part of the pancreas on the right side of your body). It typically involves the surgical removal of the head of the pancreas, a portion of the duodenum and a portion of the bile ducts.

This is an experimental type of treatment. It is a medication made of killed or weakened cells, organisms or manufactured materials, which is used to boost the body's immune system. Ideally, this will allow the body to fight and kill the cancer cells more effectively. Vaccines include whole killed cancer cells or specific proteins from the cancer.

Unable to be surgically removed. This usually means that the cancer has spread beyond the areas that can be removed surgically.

The part of the pancreas that bends backwards, hooking around two very important blood vessels, the superior mesenteric artery and vein. The word "uncinate" comes from the word uncus which means "hook."

A painless procedure in which high frequency sound waves are used to generate pictures of the inside of the body. An ultrasound devise can be placed at the end of a scope, and the scope inserted into the duodenum, providing very detailed pictures of the pancreas. This is called "endoscopic ultrasound."

This term simply refers to a "mass" or neoplasm. For example, a collection of pus is a tumor. This is a general term that can refer to either benign or malignant growths.

A clot within the blood vessels. It may occlude (block) the vessel or may be attached to the wall of the vessel without blocking the blood flow.

An inflammation of the veins accompanied by thrombus formation. It is sometimes referred to as Trousseau's sign.

The long thin part of gland in the left part of abdomen, near the spleen.

A slender hollow tube inserted into the body to relieve a blockage. For example, pancreas cancers often grow into the bile duct as the bile duct passes through the pancreas. This can block the flow of bile and cause the patient to become jaundiced. In these cases the flow of bile can be reestablished by placing a stent into the bile duct, through the area of blockage.

Excessive amounts of fat in the stool. Sometimes this can appear as an oil slick on top of the toilet water after the patient has had a bowel movement. It can be a sign that the pancreas isn't functioning well.

A classification system that is used to describe the extent of disease. Clinicians use it to predict the likely survival of a patient.

A flat, scale-like cell. Although most pancreatic cancers look like ducts under the microscope, a small fraction look like squamous cells.

A maroon colored, rounded organ in the upper left part of the abdomen, near the tail of the pancreas. This organ is part of your immune system and filters the lymph and blood in your body. It is often removed during the distal pancreatectomy surgical procedure.

A long (20 foot) tube that stretches from the stomach to the large intestine. It helps absorb nutrients from food as the food is transported to the large intestine. There are three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum. Due to its proximity to the pancreas, the duodenum is the section of the small intestine most often affected by pancreatic cancer.

An infection of the blood. This can be life-threatening and is often treated with antibiotics.

A malignant tumor that looks like connective tissues (bone, cartilage, muscle)under the microscope. Sarcomas are extremely rare in the pancreas.

Able to be removed surgically. Usually this means that the cancer is confined to areas typically removed surgically.

The use of high-energy waves similar to x-rays to treat a cancer. Radiation therapy is usually used to treat a local area of disease and often is given in combination with chemotherapy.

A thick ring of muscle (a sphincter) between the stomach and duodenum. This sphincter helps control the release of the stomach contents into the small intestine.

A forecast for the probable outcome of a disease based on the experience of large numbers of other patients with similar stage disease. Importantly, making a prognosis is not an exact science. Some patients with poor prognosis beat the odds and live longer than anyone would have predicted. Steve Dunn's Cancer Guide has an excellent article on statistics and prognoses and stories of other cancer patients.

A cancer in the organ where it started in. A primary cancer of the pancreas is one that started in the pancreas as opposed to a cancer that started somewhere else and only later spread to the pancreas.

The biochemical study of plants; concerned with the identification, biosynthesis, metabolism of chemical constituents of plants; especially in regards to natural products.

Around the ampulla of Vater in the duodenum. The peri-ampullary region is comprised of 4 structures; the ampulla, the duodenum, the bile duct and the head of the pancreas. It is sometimes difficult to tell which structure a tumor originated in. In such cases the diagnosis will be a peri-ampullary tumor.

A medical doctor specially trained to study disease processes. Pathologists make the microscopic diagnosis that is used to establish the diagnosis of cancer.

A term used to describe certain tumors which grow in finger-like projections. Pathologists use this term to describe some precancerous lesions in the pancreas (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm).

Any treatment that reduces the severity of a disease or its symptoms. Palliative care is often a part of the treatment plan for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

An oblong organ located between the stomach and the spine. The pancreas secretes enzymes needed for the digestion of food and it produces hormones such as insulin and glucagon which help control blood sugar.

A surgically created opening in an organ that can also be referred to as an anastamosis. Sometimes when surgeons remove a segment of bowel they create an ostomy to allow for the bowel contents to exit the body.

A medical doctor who specializes in the treatment of tumors. Oncologists often treat patients with pancreatic cancer with chemotherapy.

An abnormal new growth of tissue that grows more rapidly than normal cells and will continue to grow if not treated. These growths will compete with normal cells for nutrients. This is a general term that can refer to benign or malignant growths. It is a synonym for the word tumor.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy that is given to patients before surgery. Some centers feel that the use of neoadjuvant therapy improves local and regional control of disease and that it may make more patients surgical candidates.

The thin section of the pancreas between the head and the body of the gland.

An alteration in the DNA of a cell. Think of it as a typographically error in the DNA code.

A cancer that has spread from one organ to another. Pancreas cancer most frequently metastasizes to the liver. In general, cancers that have metastasized are generally not treated surgically, but instead are treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

A cancer that has the potential of invading nearby tissues, spreading to other organs (metastasizing) and possibly leading to the patient's death.

A painless method for visualizing internal organs. A tube-like machine with a powerful magnet generates images of the inside of the body. It does not involve the use of Xrays.

Normal, round, raisin to grape-sized collections of lymphocytes (white blood cells) found throughout the body. Lymph nodes are connected to each other by lymphatic vessels. They normally help fight infection, but also are one of the first sites to which cancers spread. In general, the spread of cancer to lymph nodes portends a worse prognosis for the patient. There are exceptions to this.

A primary pancreatic cancer that has spread to regional lymph nodes and/or resectable (removable) tissues. Removable tissues include some lymph nodes and parts of the duodenum and stomach that are routinely removed in some surgical treatments for pancreatic cancer.

The largest organ in the body, located in the right upper part of the abdomen. It performs many life-maintaining functions including the production of bile. The liver detoxifies the blood of drugs, alcohol and other harmful chemicals. It processes nutrients absorbed by the intestine and stores essential nutrients, vitamins and minerals. Bilirubin is a chemical produced when old or damaged blood cells breakdown. The liver chemically process the bilirubin so that it can dissolve in water and be excreted through the urine. When this process is disrupted, jaundice can develop.

A technique that surgeons can use to visualize and even biopsy (take tissue samples of) organs inside of the abdomen without making large incisions. Very small incisions are made in the belly and small tubes (called trocars) are then inserted. Gas is pumped in through one of the tubes to create enough space to work in. The surgeon inserts a small camera through one of the tubes and examines the lining and contents of the abdominal cavity by looking at the projected image on the television screen. With specially designed laparascopic instruments, biopsies and fluid samples can be taken for examination. Some surgeons feel that this technique can help "stage" a patient less invasively than with open surgery.

Yellowing of the skin or yellowing of the whites of the eyes caused by the accumulation of bile pigments (usually due to an obstruction of the bile ducts).

A hormone produced by the endocrine cells of the islets of Langerhans cells of the pancreas. Insulin acts to lower blood sugar levels.

A term used to indicate that cancerous cells are present in the duct but have not yet invaded deeper tissues.

The widest part of the pancreas. It is found in the right part of abdomen, nestled in the curve of the duodenum, which forms an impression in the side of the pancreas.

A hormone produced by the endocrine (islets of Langerhans) cells of the pancreas. When blood sugar levels are low, glucagon acts to raise blood sugar levels.

Gemzar is the trade name for the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine. It is frequently used to treat pancreatic cancer. It has been shown, in controlled clinical trials, to improve quality of life.

A green pear-shaped organ located on the right side of the abdomen just under the liver. The gallbladder is essentially a reservoir for holding bile.

A chemotherapeutic drug commonly used to treat pancreatic cancer.

The exocrine cells (acinar cells) of the pancreas produce and transport chemicals that will exit the body through the digestive system.

The chemicals that the exocrine cells produce are called enzymes. They are secreted in the duodenum where they assist in the digestion of food.

A test used to visualize and examine the pancreas and bile ducts. A tube is inserted through a patient's nose (or throat), down through the esophagus and stomach then into the small intestine (duodenum). There, a small probe is inserted into the ampulla of Vater. A dye is injected through the probe and into the pancreatic and bile ducts. X-rays are then taken to visualize the pancreatic and bile ducts. these ducts can be seen as white structures (this is because the injected dye is opaque). Because pancreas cancers often block the pancreatic and/or bile ducts, this technique can be useful in establishing a diagnosis of pancreas cancer.

A chemical that causes a reaction in other substances, in this case as a part of the digestive process.

A medical doctor who specializes in the treatment of hormonal abnormalities.

These are specialized cells that produce hormones released into the bloodstream. For example, the islets of Langerhans are endocrine cells in the pancreas that produce the hormone insulin. This hormone helps control blood sugar(glucose) levels.

Some rare tumors of the pancreas, the endocrine (Islet Cell) tumors, can produce these same hormones. It is very important that these rare tumors be properly diagnosed because it will determine the treatment and prognosis.

Surgical removal of a structure or part of a structure. For example, pancreatectomy is the surgical removal of the pancreas (or a portion of it).

The first portion of the small intestine. It is about 1 foot long. It is the part of the intestinal track that comes after the stomach.

A small anatomic structure. This is essentially a tube that carries various bodily fluids. The pancreatic duct runs the full length of the pancreas and drains into the duodenum.

The chemical in every cell that carries genetic information.

A dome shaped muscle that separates the lungs and heart from the abdomen. This muscle assists in breathing.

The disease in which the body is unable to appropriately control blood sugar (glucose) levels. This may be caused by failure of the pancreas to produce adequate amounts of insulin.

A fluid filled sac. Some tumors of the pancreas, including the serous cystadenomas and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, form cysts. Cysts have a distinct appearance in CT scans. They are important to recognize because the treatment of cystic tumors can differ from that for solid tumors.

A dye, taken by mouth or injected, that is sometimes used during x-ray examinations to highlight areas that otherwise might not be seen.

A way to image internal organs. A series of x-ray pictures taken by a machine that encircles the body like a giant tube. Computers are then used to generate cross-sectional images of the inside of the body.

The treatment of a cancer by chemicals. For pancreatic cancer these include: Gemzar (Gemcitabine), 5-flurouracil, leukovorin, taxol, and others.

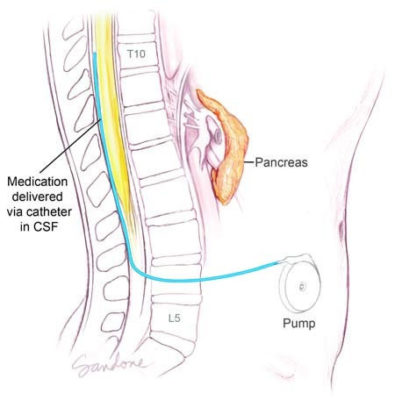

A small, flexible tube inserted into the body to inject or suck out fluids.

A cancer-causing chemical. Cigarette smoke contains a number of carcinogens.

A malignant tumor. It has the potential of invading into the adjacent tissues, spreading to other organs and may eventually lead to the patient's death.

A dramatic weight loss and general wasting that occurs during chronic disease.

A blood marker for pancreas cancer. It is not a good screening test for diagnosing possible pancreas cancers in individuals without symptoms. Instead, it can be useful in following the progress of patients known to have a cancer by measuring how their cancer is responding to treatment.

The middle part of the pancreas between the neck and the tail. The superior mesenteric blood vessels run behind this part of the gland.

The removal and microscopic examination of a small tissue sample.

A duct that carries bile from the liver to the intestine. This term may refer to the hepatic, cystic or common bile duct.

A green fluid produced by the liver that helps digest fats. It is transported from the liver to the duodenum by the bile duct. When the flow of bile is blocked, patients may become jaundiced (yellow skinned).

Tumors which are non-cancerous. These generally grow slowly and do not invade adjacent organs or spread (metastasize) beyond the pancreas.

The collection of excess amounts of fluid in the abdominal cavity (belly). It often is a sign that the cancer has spread to either the liver or to the portal vein that goes to the liver, or that the cancer involves the internal lining of the abdomen. If normal liver function is affected, a complex set of biochemical checks and balances is disrupted and abnormal amounts of fluid are retained.

The large artery that carries oxygen-rich blood from the heart. From the heart it arches backwards and descends into the abdomen where it gives off many branches to supply the organs. The superior mesenteric artery is a major branch of the aorta that can be involved by pancreatic cancer.

A radiographic technique used to visualize blood vessels. A contrast medium (a dye) is usually injected into the vessels to make them appear white on the x-rays.

A condition marked by a diminished apetite and aversion to food. Often results in physical signs of wasting.

A condition characterized by a deficiency in red blood cells. This can lead to fatigue among other symptoms.

A surgical joining of two hollow structures. It is similar to attaching two ends of a garden hose. For example, a gastrojejunostomy is a surgical procedure that connects the stomach and the jejunum (small intestine.)

This widening of the pancreatic duct as it reaches the duodenum is an landmark for physicians. It is where the bile duct and pancreatic duct join before draining into the duodenum (small intestine). Tumors in the head of the pancreas may squeeze this duct partially or completely closed. This can lead to problems with digestion and jaundice.

Chemotherapy given to patients after their cancers have been surgically removed. It is a secondary treatment given to supplement surgical treatment. (see Neoadjuvant chemotherapy which is chemotherapy given before surgery)

A benign (non-cancerous) tumor made up of cells that form glands (collections of cells surrounding an empty space).

The form of cancer that most people are talking about when they refer to "cancer of the pancreas." These tumors account for 75% of all pancreas cancers.

Microscopically, adenocarcinomas form glands. These tumors can grow large enough to invade nerves which can cause back pain. They also frequently spread (metastasize) to the liver or lymph nodes. If this happens the tumor may be considered unresectable.

A pus-filled cavity. Usually caused by an infection.

The portion of the body between the diaphragm and the pelvis.